Who Gets Scammed?

Some ripoffs mean giving up $50,000 to a stranger in a van. Some mean fake Facebook job listings, exploitative MLMs, and a host of unpaid work schemes aimed at moms.

Periodically, a bubbly-sounding woman with a generic profile picture will post in one of my moms-only Facebook groups, offering a job that sounds almost too good to be true.

“Hey ladies!” reads the archetypical post. “My job is hiring motivated mommas for part time work from home.” The post (I’ve encountered many variations by now) invariably goes on to list incentives like “full benefits,” “paid training,” “flexible hours,” and pay in the range of $25-30 dollars per hour. Would-be applicants are encouraged to apply via Facebook message.

Sometimes the comments on these posts are populated by women expressing interest. Other times, commenters warn that the message sounds like a scam. And on at least one occasion in a group I’d joined, a local woman commented that she’d been taken in by the job offer, but soon learned that her new job involved moving deposits into and out of her checking account, likely as part of a money laundering scheme.

Financial scams are in the limelight this week after New York Magazine financial advice columnist Charlotte Cowles published an essay admitting to having been tricked into withdrawing $50,000 from her bank account and handing it to a stranger in a van, under the mistaken belief that he was a CIA agent. Many people fall for scams, the essay argues, and while—I’ll call it—I do not think I would have been persuaded by this racket, it’s nevertheless true that everyone can be made more susceptible under certain combinations of desperation and hope. Cowles writes that she fell for the scam, in part, because she feared that criminals would harm her son.

The scammers luring moms with “work from home” gigs are exploiting a similar fear. Their job listings are tailored to look like financial lifelines for mothers whose primary work is unpaid, home-based childcare. And while laundering stolen money through an unsuspecting Facebook mom’s bank account is flatly illegal, other, less-criminal enterprises target the same women though extractive programs like multi-level marketing schemes, which dangle the hopes of financial independence and flexible scheduling for moms who can’t expect such accommodations from a typical 9-5.

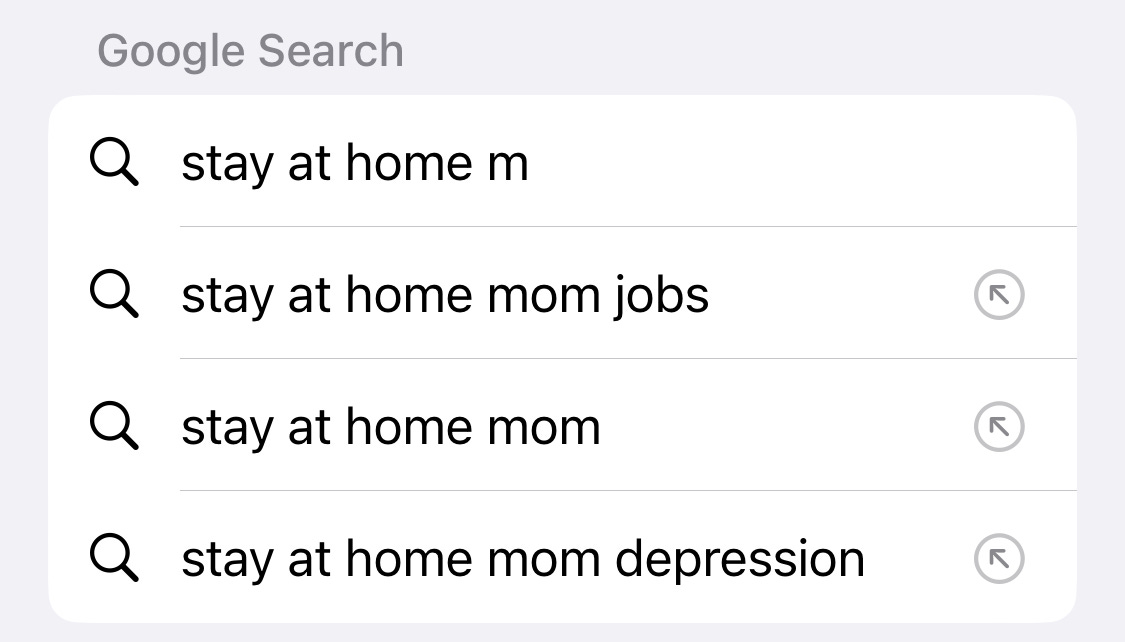

Despite conservative branding exercises that cast domestic labor as mothers’ natural role, moms who care for their children full-time at home often look for additional paid work, either out of financial necessity, desire to build one’s qualifications, or to participate more fully in a culture that primarily values people by their paid professions.

(Here, incidentally, are the suggested searches that appeared when I started Googling “stay at home mom” from my phone. Full-time childcare is valuable and meaningful work, but a country that divorces that work from wages, public support, or even full access to public life is ensuring that many of those caretakers will want more in the way of financial or social support.)

The straight-up scams that appear in neighborhood mom groups promise high pay and “flexible hours” as a solution to these parents’ financial struggles. But a very slim minority of people will end up handing over their banking details, or $50,000 in cash, if courted by a scam artist. Far more popular, especially among mothers, are more-legal schemes that attract recruits by also appealing to social isolation.

Multi-level marketing companies like Arbonne and LuLaRoe recruit women to sell their products and (more lucratively) to recruit friends to sell those products. The recruitment process requires participants to buy the company’s product at wholesale, in the hopes of reselling it for profit. Almost no participants break even, let alone strike it rich.

Some MLM participants end up bankrupt—worse off than Cowles, who had additional savings and plans to take a tax writeoff for at least some of the $50,000 theft.

Women represented three-quarters of MLM sellers in 2019, due in part to MLMs’ tendency to prey on stay-at-home mothers’ isolation and desire for community, HuffPost reported that year.

“Several corners of the internet have become devoted to connecting mothers with each other, and MLMs are tapping into these networks to make their sales and recruitment,” one expert told HuffPost of the companies’ reliance on womens’ support networks.

Like the bogus “data entry” job scams that recruit Facebookers into money-laundering rings, MLMs also promise flexible schedules that allow stay-at-home moms to clock in from home, or after their children are asleep—concessions that many conventional companies do not make.

Some MLMs are explicit in their courtship of mothers with limited resources. In the 2021 documentary series LuLaRich, LuLaRoe co-founder Mark Stidham boasts of tapping the supposedly underused resource of stay-at-home mothers’ labor.

“If you want to create incredible wealth, identify an underutilized resource,” Stidham says. “And you know what? There is an underutilized resource of stay-at-home moms.”

It’s a telling quote—dawg, you’re so close to accidentally re-inventing Marxism through negation—and one that reveals the devaluation of the domestic work that underpins the American economy. Those “underutilized” moms are working! They’re minding children, making food, and cleaning house, all tasks that would otherwise need to be delegated to paid professionals. Their labors enrich Stidham indirectly, providing the country’s economic foundation and raising its future workers at a deep discount that is seldom acknowledged in national budgets or in the biographies of “self-made” entrepreneurs.

Writer Meg Conley took the occasion of the LuLaRich documentary to excoriate what she described as an American prosperity gospel that champions personal advancement at the expense of the often marginalized workers who make it possible.

“White feminists have bought into a pyramid scheme too! I’ve written about this before but America is a pyramid scheme,” Conley wrote in 2021.

“It relies on people buying into the American Dream and then working hard to get to the top. But of course - almost no one does. Beneath each successful person in America is a downline of unpaid and underpaid labor. As I wrote in this piece on American motherhood as an MLM, if we included the unpaid production that takes place in the home and the community to our yearly gross domestic product, researchers say it would grow by at least 23%, or more than $4 trillion.

That’s such a fucking scam! It can be easy to side-eye a person who hands over their bank details to a fake job recruiter on Facebook, or who buys $6,000 of unsellable LuLaRoe leggings with the goal of “starting her own business.” But it’s harder to mock in the context of a work culture that is often hostile to mothers and their needs, where a pie-in-the-sky job listing is the only gig offering hope.

In her New York column, Cowles quotes her brother, a lawyer, who likened her scam experience to a coerced criminal confession.

“I read enough transcripts of bad interrogations in law school to understand that anyone can be convinced that they have a very narrow set of terrible options,” he said. Maybe that’s true. Also, some people genuinely have few easy options.

It’s not lost on me as I write this newsletter that I’m doing so on Substack, a platform that takes a not-insignificant cut of my earnings. I know that, like an MLM, Substack showcases its rare high-earning writers (many of whom, like many successful MLM participants, were early members) to motivate new writers to sign up and self-publish for far less than market rates, under the dream of being one’s own boss and eventually attracting enough paid subscribers to hit the big time.

Like the busy mom applying to a Facebook scam because she wants a little extra money from twice-weekly work, I’m not anticipating a full salary from this blog. That would be unrealistic.

Unless. Well. It works for some people.

Maybe it will work for me.

Hey, thanks for reading MomLeft! Want to help Make It Work? Toss me a subscription or forward this newsletter on to a friend. For $50,0000, you could buy monthly subscriptions for you and 6,519 pals.