Hot Take

Air-conditioning is expensive. So are the costs of heat-driven learning loss, research proves.

In 2020, economists set out to study the effects of extreme heat on students, and the effects of heat-related learning-loss on the economy. Their findings were stark: even a one-degree increase in temperature during a school year resulted in students learning approximately one percent less.

The learning losses, which economists translated into thousands of dollars in lost future earnings for students, disproportionately affected Black and Hispanic students, who were more likely to attend overheated schools. But the paper also pointed to an obvious, cost-effective means of treating the problem. Air-conditioning, which many schools still lack, improves academic achievement so efficiently that it nearly pays for itself in students’ future income, alone.

A heat wave is currently hammering large parts of the U.S., including those where school is in session. Students empirically cannot learn at normal rates during these heat waves, which are only projected to intensify with further climate change. It’s not just ethical to keep schools cool—it’s vital to education. But despite the documented harms of extreme heat, many schools are insufficiently air-conditioned today, and even less prepared for warmer school years to come. Outfitting schools for climate change is admittedly pricey. Keeping kids in the heat is even costlier.

We know that extreme heat hurts kids’ ability to learn. The 2020 study, and previous research from Harvard University, drew data from a set of 10 million students’ test scores. Even after controlling for other weather events and local economic conditions, the research was clear: students scored measurably worse in exams after a hot year than they did after a cooler year.

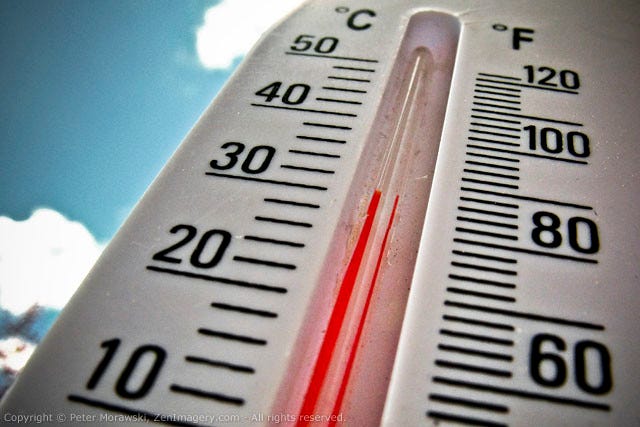

In schools without air-conditioning, a 1°F increase in temperature during the school year resulted in test scores that showed students falling behind by approximately 0.2 percent of a standard deviation. (Students started experiencing learning loss above 70°F.) That figure might appear small—researchers calculated it to represent approximately one percent of a student’s annual education—but it compounds quickly.

“Relative to school days with temperatures in the 60s (°F), each additional school day with temperature in the 90s (°F) reduces achievement by one-sixth of a percent of year’s worth of learning,” they found. “A day above 100 (°F) has an effect that is up to 50 percent larger.”

Those learning losses add up over years. Researchers found that hot years create a tailing effect in poor test scores “so that the cumulative effect of elevated temperature over multiple school years is substantially larger than that of a single school year.”

And in a heating world, those losses risk becoming a norm. Last year, for instance, global temperatures hit a grim benchmark when they reached an average 3.6°F (2°C) above pre-industrial levels. “For the average student, a sustained increase in temperature of 3.6°F (2°C) lowers achievement gains by two percent of a standard deviation, or approximately seven percent of an average year’s worth of learning,” researchers found.

By 2050, when median climate change projections estimate a 5°F increase, the researchers project an approximately 10 percent average annual learning loss.

Black, Hispanic, and low-income students were disproportionately likely to suffer learning loss, the paper found. Those students were more likely to attend schools that had been flagged as lacking adequate air-conditioning, and were less likely to have access to tutors and home air-conditioning that could help offset the toll of studying in an overheated classroom.

“Experiencing 1°F hotter school years over the past four years has a nearly 80 percent larger impact on black and Hispanic students than on white students,” the researchers found. Those racial learning gaps are only expected to widen if climate change continues unabated.

The quickest equalizer is air-conditioning. Researchers found air-conditioning to offset 73 percent of heat-based learning loss. Based on students’ projected earnings relative to their test scores, the researchers calculated that air conditioning would offset heat-driven income losses on an average of “$1,060 per student, $26,500 per classroom, or just over $1 million per high school.”

Installing air-conditioning is expensive—a cost all too familiar to many schools that were constructed in cooler decades. A 2021 study by the Center for Climate Integrity found that

more than 13,700 public schools that did not require air-conditioning in the 1970s require it today. The CCI estimated that outfitting all schools with adequate air-conditioning would cost more than $40 billion.

Lack of public funds have led some parent groups to raise their own money for air-conditioner installation. In cities like New York, where income varies dramatically between neighborhoods, the parent-led charge has resulted in wealthier districts installing air-conditioning while some lower-income districts still await slower, city-funded upgrades.

Still, a less-piecemeal campaign to outfit U.S. schools with air-conditioning could easily justify its own costs. In 2021, the year CCI priced air-conditioning upgrades at $40 billion, the U.S. had just under 49.4 million public school students, placing the cost of a national project at around $800 per student. Weighed against the additional $1,060 a student is estimated to earn from an air-conditioned school, those infrastructure upgrades look pretty obvious.

Even by a “conservative estimate” of recovered earnings relative to installation costs, the authors of the 2020 paper found that “the amortized cost of school air conditioning to be approximately $125,000 per school per year, or $125 per student per year for a 1,000 person school.” For each increase in test scores (and in subsequent earnings) that’s still more cost-effective than other pro-student measures, like smaller class sizes.

Air-conditioning isn’t a panacea. The researchers found that it would only prevent 73 percent of learning loss. It also contributes to further climate change; air-conditioners are the source of an estimated four percent of greenhouse gas emissions. While air-conditioning addresses the symptoms of climate change, schools must also help combat its causes.

The Chicago Teachers Union, for instance, unveiled a push for climate-friendly technology in schools last Friday. Under the new proposals, the schools would install solar panels and heat pumps, switch to electric buses, and grow plants that would help provide shade and control stormwater. By Monday, the city was experiencing a record-breaking 97 degree heat wave.